Certain things blur the boundaries of reality. Like a phone that can only connect to one number. Like the number that phone dials, which is also listed as the phone number on the TripAdvisor page for Echo River in Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave National Park. Like the prerecorded message that plays when you dial that number, which says, “If you don’t remember dialing this number at all, press 5,” before launching into facts that all sound like thinly veiled urban legends. Like a retrospective for an artist who seems to have never existed, or a community television broadcast that seems to end with a ghost in the machine.

This web of ephemera, which extends from the world we live in to the one on the other side of the screen, would seem to be the work of a major company, like the alternate reality game that accompanied the release of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight and sent 11 million people all over the world in search of the Joker. What actually ties all these threads together is much smaller: Kentucky Route Zero, an indie developed by just three friends that’s also—at last after nearly 10 years of development and sporadic partial releases—the best game of 2020.

The bestselling games of the past few years have all been big, in every sense of the word. 2018’s Red Dead Redemption 2 boasted endless frontiers and side quests to get lost in as well as an online multiplayer component with completely new stories to explore; it even featured a “cinematic mode” that showed off just how slick and realistic its graphics are. 2019’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare touted similarly vast battlegrounds plus 4K resolution, multiplayer support for up to 64 players, several “seasons” of added content, and what it termed a “Realism” mode. And the biggest hit of 2020, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, not only allows players to visit one another’s islands, send letters, and customize almost everything, but also introduces new features and events as the seasons change. The emphasis, with all of these games, is on more.

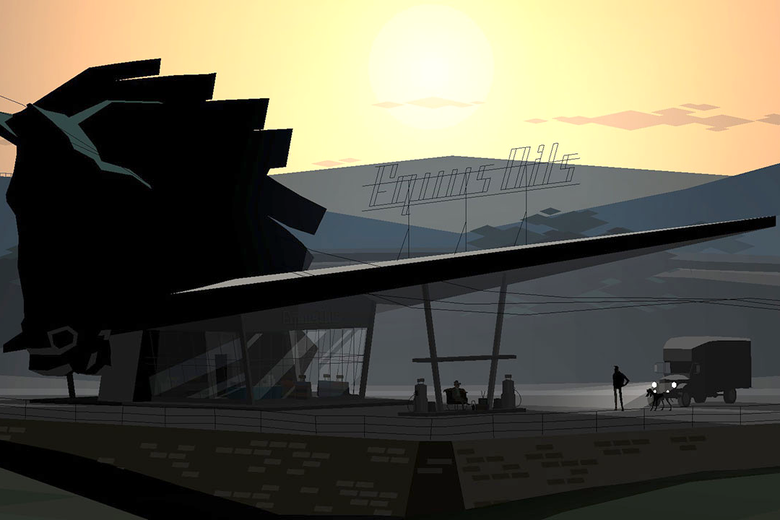

In Kentucky Route Zero, there are no weapons, no skill trees, no items to collect, and no customizable characters, and there is no open world. The only mechanic is to point and click. Following the cursor, characters—who are animated so deceptively simply that they almost look 2D—can move from place to place, either on a set stage or via a black-and-white map, and sometimes engage in conversation. It never gets more complicated than that, but the elements—the art, the writing, the music—all coalesce into an eerie, unforgettable experience.

Cardboard Computer developers Jake Elliott, Tamas Kemenczy, and Ben Babbitt have been putting Kentucky Route Zero together piece by piece over the course of the past decade. Despite its apparent simplicity, the game tells a trenchant and startlingly intimate story about contemporary Americana, mining intergenerational trauma and the ins and outs of platonic, romantic, and familial love to create a work that any Triple-A publishers would be jealous of. The “more” that most often characterizes modern gaming isn’t present in the game’s features, but in what it has to say. Its ending, rather than providing a grand finale or boss battle, plays almost like an elegy.

The first character you meet in Kentucky Route Zero is Conway, a truck driver seeking a mysterious highway in Kentucky known as “the Zero” in order to make his final delivery. The task, and how to achieve it, seems simple enough: Talk to people to find out what they know, complete a few stray errands in order to collect a little more information. Point and click.

But those clicks stack up. Every character you meet is burdened by some kind of debt or loss, the theme echoed in every location you pass through: a farm that’s been foreclosed on, a mine abandoned after a deadly flood caused by the negligence of the company in charge.

The more you explore—and as some of those characters become playable and more central to the narrative—the stranger Cardboard Computer’s vision of Kentucky becomes, with appearances from sentient robots and talking skeletons. But the weird, wonderful places the game goes remain entrenched in contemporary America. “We wanted to make the game about what’s going on where we live,” Elliott explains. “I think magical realist fiction is always super grounded in the realities that it’s written in—it’s always very political as a genre. I’ve thought a lot about how to translate that, how to translate One Hundred Years of Solitude to Kentucky. What would the real issues be with that? What would the magic be?”

The issues at hand are obvious. Though it feels too simplistic to say that Kentucky Route Zero has an antagonist, the exploitative energy company around which much of the action revolves leaves only desolation behind. In the company’s wake are an empty mine filled with ghosts and countless stories about seemingly innocuous contracts that have resulted in debt that has lasted beyond the grave. Its presence tips the story into tragedy explicitly grounded in the game’s setting. As Elliott notes, “you couldn’t have an apolitical representation of a coal mine in Kentucky.”

But the game’s magic is a little harder to define. The best moments come when the slow seeping of the supernatural into the story reaches something of a critical mass—and gives way to moments of pure fantasy. In a sequence befitting David Lynch, the roof of a dive bar floats away, leaving behind just the clouds and the stars as a band performs. In another scene, the wood boards of a house’s walls peel away one by one to reveal the next stage of the adventure. These beautifully rendered, ambitious set pieces are all the more remarkable for being a part of an indie game rather than the work of an established studio.

The full, final version of Kentucky Route Zero was released in January 2020 by Annapurna Interactive, the video game branch of the same company that’s released such gourmet fare as the movies The Master and If Beale Street Could Talk, the miniseries adaptation of The Plot Against America, and the acclaimed gothic video game What Remains of Edith Finch. But for years before that, Cardboard Computer handled every aspect of production as an independent operation. And though they met in Chicago, Kemenczy, Babbitt, and Elliott are now scattered across the United States and worked almost entirely remotely on the game. That independence allowed them to create a title that doesn’t hew to any of the blockbuster conventions of the medium, but it came with a catch. For years, Kentucky Route Zero felt like a point-and-click version of A Song of Ice and Fire: an epic that might never be finished.

Though it’s common for games to experience delays leading up to release, Kentucky Route Zero has forged its own path, with its creators doling it out in parts for the past decade. Unlike living games like Fortnite and World of Warcraft, Kentucky Route Zero wasn’t adding more and more missions and shiny objects to keep players engaged. Rather, the game was a serial, comprising five “acts.” But it was never clear when, exactly, the next act might come along. After a Kickstarter in 2011 (in which Elliott and Kemenczy promised that new installments would be released “every 2-3 months” and narrowly exceeded their $6,500 goal), the first two chapters debuted in January and May of 2013, with the third following in 2014, and the fourth in 2016. When fans got itchy for the final act—and Cardboard Computer ran out of sloth GIFs to use as responses on Twitter— they cobbled together a hotline, 1-858-WHEN-KRZ, to assure players that the game would eventually be coming. (The Cardboard Computer Twitter icon, meanwhile, remains a sloth.)

Appropriately, Kentucky Route Zero is a work born out of lifelong fascination. As a child, Elliott played a game called Colossal Cave Adventure. Created by Will Crowther, the game (generally acknowledged to be the precursor to all adventure games) serves as a loose guide through Mammoth Cave, the 400-mile underground system that runs under Kentucky, through a relatively simple text adventure. Though Elliott grew up on the West Coast, Crowther’s work stuck in his memory. His first collaboration with Kemenczy—whom he met while studying what they refer to as “software art” at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—was a text adventure game called Sidequest, in which the player takes on the role of Crowther himself.

The pair’s initial idea for Kentucky Route Zero was relatively simple. It would be a platformer in the vein of Metroid or Castlevania, but it would swap out the killing and gunfire to focus on dialogue. Travel companions, meanwhile, would provide different power-ups and advantages. As development progressed, however, the game started to change alongside the story they were trying to tell—as well as their sense of what it was actually possible to create as a two-person team.

The art style, which favors painterly polygonal abstractions over strict realism, came out of figuring out what Kemenczy could feasibly construct on his own; its resulting alteration of the game’s spatial sense moved the game away from being a platformer. Characters became placed as if on the stage of a play, interacting with a set space rather than just breezing from one setting to the next. That wasn’t the only way Kentucky Route Zero became less like a video game as its development progressed. The idea of gaining power-ups, common in most games, was discarded, making Kentucky Route Zero something more like Colossal Cave Adventure—a space to explore and take in rather than win or lose. Luckily, their original Kickstarter backers welcomed the changes. Kemenzcy says that some comments on their original trailer were disparaging of the more gamey aspects: “People were like, ‘You had me up until that.’ ”

When they started making Kentucky Route Zero, Elliott and Kemenczy thought they could finish it on their own. Babbitt, who had transferred to the school to continue studying music, was initially hired to write only a handful of songs for the game. But after a year and a half of initial development—during which Babbitt heard nothing from the pair—it became clear that Babbitt’s work wasn’t done. They needed more songs, having used everything Babbitt had given them on the first act, and they needed someone to handle the sound design too. As with every other aspect of the game, Babbitt’s role kept growing as the horizon fell further and further back.

“I think we’ve just maintained an emphasis on the importance of allowing the project to develop naturally over however long a period of time that would take,” Babbitt said, explaining the long timeline. It was only ever the three of them working on a game that’s titanic in intention and in scope. The years that have passed have been spent not only putting Kentucky Route Zero together but keeping themselves from burning out. “I can’t imagine anybody who, working on a project for this long, wouldn’t feel fatigued at one point or another,” Babbitt says. “I choose not to think about it as working on one game,” Kemenczy adds. “It’s more inspiring or more motivational for me to think about it as: We’re working or continuing games in an anthology or a universe. It got kind of burdensome for a while, but then we looked back and we were like, ‘Well, we actually made quite a number of games.’ ”

How vast is Kentucky Route Zero? So vast that it doesn’t just include the five main acts but five so-called interludes as well. Each expands on Kentucky Route Zero’s mythology but plays around with and breaks from the format of the main storyline. Like the game itself, the interludes have ballooned since their conception (and added to the time it’s taken to put the whole game together). One of them, titled Limits and Demonstrations, was born out of a practical concern— the team needed to test graphics cards to ensure that what they were building could actually be played—but quickly grew into its own little game. Eventually, the interludes became not just a way of experimenting with form and resisting burnout but a way of fleshing out the world the developers had created for the sake of their game, and of keeping the world alive and breathing for a moment more.

Prior to the game’s full release, which bundles the interludes up with the game’s main acts, the five smaller installments were simply littered across the internet, released as separate downloadable games or popping up on eBay and YouTube, traceable to their origin by just the faintest trail of breadcrumbs. Unlike most contemporary releases, which thrive upon new features and explosive advancements in gameplay, Kentucky Route Zero has almost gone out of its way to hide just how deep it is. It’s a growing creature, to be discovered.

But as satisfying as the full bundle is, the interludes can also break loose from the environment in which they were created and take on meaning for people who may not know of the game or have any interest in video games, period. One interlude, Here and There Along the Echo, the aforementioned phone number, “gets a lot of traffic,” Elliott says. “I think most of those people have no idea about Kentucky Route Zero. It’s totally not part of the experience for them. It’s on a few internet lists of haunted phone numbers or creepy phone numbers—that’s how they find it, and that’s how they think about it.”

That blurring of boundaries is present in every aspect of their work, from the way that Kentucky Route Zero is structured—in Elliott’s words, there’s no “right answer to the puzzle”—to the setting itself. Like the game, which can’t quite be pigeonholed as belonging to a single genre, Kentucky exists in a state of in-between too. During our conversations, the trio place the state in the Midwest, the South, and the “Midwestern South.” “That’s one of the things I like about it,” Babbitt says. “It’s on the border of a lot of things in a lot of ways.”

That the game is finished now feels bittersweet, its creators say. There are no more design changes to implement, and there’s nothing left to overhaul. But a decade is a long time to spend on one project. “I made the music for Act 1 maybe up to a year and a half before it came out,” Babbitt says. “I was much younger then, and I’m using radically different tools than I was at that time. But it’s still important to me for the music to feel like it all makes sense together in some way.” On top of that, the problem isn’t just that it’s all had to be cohesive despite being made across such a long span of time but that it’s had to remain faithful to acts published four to seven years ago. No backward revision is possible. “I had a lot of anxiety writing the last part,” Elliott says, “for the last act not matching the tone of the first act, which was nine years later.”

Working on the graphics side, Kemenczy describes his process as having been slightly easier. Unlike Elliott and Babbitt, who were working with more nebulous mediums, Kemenczy set limits for himself early on in terms of how things would look. More significantly, he’s ready to let go. “It feels good to be done with it,” he says. “Some people say they have a sort of postpartum depression after finishing a huge project like this, but for me it’s just a huge relief to be able to close it.” Elliott and Babbitt have slightly more mixed feelings. “I feel like I have some weird identity stuff for us as a team around finishing this project,” Elliott says. “We’ve made this one big game, and you can like it or not like it, but it’s our work. Now I’m trying to figure out who we are.” Babbitt, who considers himself “the opposite” of Kemenczy, feels similarly: “I really have trouble letting go. My tendency is always to go back and revise, to give in to the perfectionist impulse. And when I finish something, I tend to get really pretty depressed after. There’s always some aspect of a hard crash, an identity crisis element especially. And I’ve never worked on anything for this long.”

They already know what they’ll work on next, though they won’t give away any details. Still, if Kentucky Route Zero is proof of anything, it’s that nothing made by Cardboard Computer is quite as simple as it may seem. Though the game’s story is linear, there’s a dizzying amount of exploration that can be done. Certain choices and dialogue options will open up new paths. Take a wrong turn down a hallway, and you’ll find a whole host of details that add to the sense of place but don’t necessarily progress the story in any way. Simply put, there’s so much packed into Kentucky Route Zero that swaths of it will likely go undiscovered—but that’s by design.

“It’s a world, isn’t it?” Elliott reasons. “You have to be able to miss stuff for it to feel alive.”

"best" - Google News

December 09, 2020 at 05:45PM

https://ift.tt/37PWtx1

The Strange Story Behind the Best Game of 2020 - Slate

"best" - Google News

https://ift.tt/34IFv0S

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Strange Story Behind the Best Game of 2020 - Slate"

Post a Comment